Having been introduced 30 years ago, SATs (‘standardised assessment tasks’) are one of the most prominent features of primary education in England, yet they remain as controversial now as they were back in the early 1990’s. To their supporters, SATs are an invaluable tool for measuring the attainment and progress of both pupils and schools in an objective and consistent manner across England’s 16,800 state-funded primary schools. To their critics, SATs are a stressful, unnecessary and burdensome way to monitor pupils and schools and should therefore be scrapped. In recent years, SATs for 7-year-olds and 11-year-olds have been joined by other formal nationwide assessments. A ‘phonics check’ was created for Year 1 pupils in 2012 to test their basic reading skills, and the current academic year will see two new assessments rolled out: a ‘reception baseline assessment’ to test the cognitive skills of reception pupils and an online ‘multiplication check’ to assess Year 4 pupils on their multiplication tables up to 12 x 12.

Having been introduced 30 years ago, SATs (‘standardised assessment tasks’) are one of the most prominent features of primary education in England, yet they remain as controversial now as they were back in the early 1990’s. To their supporters, SATs are an invaluable tool for measuring the attainment and progress of both pupils and schools in an objective and consistent manner across England’s 16,800 state-funded primary schools. To their critics, SATs are a stressful, unnecessary and burdensome way to monitor pupils and schools and should therefore be scrapped. In recent years, SATs for 7-year-olds and 11-year-olds have been joined by other formal nationwide assessments. A ‘phonics check’ was created for Year 1 pupils in 2012 to test their basic reading skills, and the current academic year will see two new assessments rolled out: a ‘reception baseline assessment’ to test the cognitive skills of reception pupils and an online ‘multiplication check’ to assess Year 4 pupils on their multiplication tables up to 12 x 12.

As evidenced by the last General Election campaign, debates over the importance and usefulness of primary school assessments (and the associated accountability system) are still as strongly contested as ever. The collapse of all national assessments in 2020 and 2021 due to the tragic outbreak of COVID-19 has revived these disagreements once again, with both supporters and critics of SATs claiming that the events of the past 18 months have demonstrated why they were right all along. In truth, England’s recent performances in international comparative tests appear to suggest that some reforms to primary assessments over the past decade are indeed bearing fruit, but those same tests show that England remains well short of being a world-class education system. Consequently, after analysing the available research evidence on the full range of primary school assessments being used in the 2021/22 academic year, this report set out to design a new assessment and accountability system for primary education that would deliver the following improvements:

- Promoting high standards for pupils in all year groups in terms of their progress and attainment

- Reflecting the contribution that schools make to their pupils’ education in a fairer and more proportionate manner

- Ensuring that the assessment system supports high-quality teaching and learning rather than encouraging excessive test preparation

- Providing more accurate information on the performance of pupils and schools as well as performance at a national level

- Reducing the assessment burden on teachers and schools

The reception baseline assessment (RBA)

At present, the progress of primary school pupils is measured by the improvement shown between their Key Stage 1 (KS1) SATs results in Year 2 (age 6-7) up to their Key Stage 2 (KS2) SATs results in Year 6 (age 10-11). As far back as 2013, the Department for Education (DfE) had questioned this arrangement, pointing out that “a baseline check early in reception would allow the crucial progress made in reception, year 1 and year 2 to be reflected in the accountability system and would reinforce the importance of early intervention”. Many stakeholders agreed that pupil progress should be measured from the earliest possible point, leading the DfE to announce that they would replace the current KS1 starting point with a ‘reception baseline’ to measure pupil progress from age 4 up to KS2 SATs.

Although the DfE’s first attempt to develop a new ‘reception baseline’ test was aborted after a pilot study in 2016, the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) was eventually contracted in 2018 to create the new RBA. The development of this new assessment involved over 7,000 primary schools, and the results of the subsequent pilot study were encouraging. The RBA is an activity-based assessment of language, communication and literacy (e.g. early vocabulary and comprehension) as well as mathematics (e.g. early understanding of numbers and patterns). Of the practitioners (mostly reception teachers) who tested the RBA, 82 per cent rated the mathematics tasks as ‘satisfactory’ or above and 65 per cent of practitioners trialling the literacy, communication and language tasks considered them to be at least ‘satisfactory’. What’s more, 84 per cent of practitioners rated the children’s interest and enjoyment of the tasks as at least ‘satisfactory’, and 89 per cent said that the children’s understanding of the tasks was ‘satisfactory’ or better.

Not all observers were convinced, though. A recent report from the British Educational Research Association criticised the Government’s plans to use the RBA as the starting point of a ‘progress measure’ for the whole of primary education. For example, the time lag between the RBA at age 4 and KS2 SATs at age 11 raises the question of how useful the results of the new 4-to-11 progress measure will be, seeing as many aspects of a primary school could change dramatically over six or seven years (e.g. a new head teacher and / or school leadership team). Presenting this new progress measure to parents as an indication of the level of progress that their child is likely to make at a school now (as opposed to several years previously) will be a questionable proposition.

Numerous other factors could distort the new progress measure. 20 per cent of primary pupils in England move school at ‘non-standard’ times of year, meaning that these pupils will end up being educated in a different school from the one in which they completed the RBA. It remains unclear how the DfE’s new progress measure will accommodate this degree of pupil mobility. In addition, any school with more autumn-born pupils could inadvertently be made to look worse in terms of ‘pupil progress’ because summer-born children will on average have lower levels of attainment and thus potentially be able to demonstrate more ‘progress’ over the next seven years. Furthermore, in the absence of KS1 SATs, many primary schools will not deliver any other formal assessments after the RBA before their pupils move onto another school (e.g. switching from an infant school to a junior school at age seven). As a result, the introduction of the RBA means there will no longer be any measure of pupil attainment or progress for thousands of primary schools. An Education Select Committee investigation in 2017 also heard that the existing progress measures from KS1 to KS2 had been designed in such a way that they encouraged “deflating [KS1] results to demonstrate greater progress at the end of KS2”, yet the Government has not outlined how it will prevent this happening with the RBA in future. Such concerns do not undermine the validity of the RBA as an assessment of reception pupils, but they illustrate the pressure that will be placed on the RBA as it is delivered in primary schools from this year.

The impact of SATs on teachers and schools

At present, KS2 SATs in Year 6 include three tests (reading; grammar, punctuation and spelling; mathematics) that are marked externally. Alongside these tests, teachers assess their pupils’ writing skills. KS1 SATs only cover mathematics and reading (with an optional grammar, punctuation and spelling test) and are marked by their teachers, along with teacher judgements of pupils’ level in science, writing and speaking and listening.

There have been many investigations of testing and assessments by parliamentary committees spanning multiple governments, yet they invariably conclude that national testing can play an important role in providing objective and consistent data about the standard of education across different schools. However, problems quickly arise when the data from any single test is used for too many different purposes, with one such Committee being told in 2008 that Key Stage tests such as SATs were being used for 14 separate purposes at the time. The same Committee also heard that a poor set of SATs results may result in “being perceived as a “failing school”, interventions by Ofsted and even closure in extreme cases” – illustrating how the high-stakes accountability system for primary schools is closely linked to SATs results.

One of the most worrying effects of this high-stakes accountability system is ‘teaching to the test’, whereby teachers ‘drill’ their pupils in a subject on which they will later be tested and devote a high proportion of time to test preparation, exam techniques and even question-spotting. The aforementioned Committee in 2008 “received substantial evidence that teaching to the test …is widespread” and that “test results are pursued at the expense of a rounded education”. One survey found that for four months of the final year at primary school, teachers were spending nearly half their teaching time preparing pupils for KS2 tests.

In 2010, the Coalition Government expressed their concern that “especially in year six, there is excessive test preparation – with some children practising test questions for many weeks in advance of the tests.” Similarly, the Education Select Committee in 2017 heard evidence that ‘teaching to the test’ could mean KS2 SATs results were “severely inflated in being far larger than true gains in students’ learning”. The Committee recognised “the pressure that schools are under to achieve results at Key Stage 2” and that “many teachers reported ‘teaching to the test’ …as a result of statutory assessment and accountability” – a point made by teaching unions almost a decade earlier when they told the 2008 Committee it was “hardly surprising that the focus is on ensuring that students produce the best results.”

A narrowing of the curriculum is another side-effect of the current assessment regime in primary schools, as non-tested subjects such as sport, art and music risk being neglected and having their curriculum time reduced to make more room for preparing for the next test. The Education Select Committee in 2017 cited evidence from Ofsted that most primary schools were spending four hours or more a week teaching English and maths, yet around two thirds of schools spent only one to two hours per week teaching science, and around a fifth spent less than one hour. In 2018, Ofsted reported that they had seen “curriculum narrowing, especially in upper Key Stage 2, with lessons disproportionately focused on English and mathematics” and “sometimes, this manifested as intensive, even obsessive, test preparation for Key Stage 2 SATs that in some cases started at Christmas in Year 6.”

Numerous committees and reviews in recent years have also expressed misgivings about whether performance tables (‘league tables’) give a fair reflection of what a primary school has contributed, particularly when schools operate in different contexts and sometimes with very different pupils. At the same time, the current assessment and accountability system has repeatedly been found to distract schools from improving teaching and learning as well as encouraging a ‘risk-averse culture’. Finding more accurate and reliable ways to measure pupil progress in a fair and proportionate manner would therefore represent a major step forward.

The impact of SATs on pupils

In 2007, the independent Cambridge Primary Review (CPR) found that “for pupils in years 2 and 6 the notion of SATs looms large in pupils’ minds” and “some pupils feel that their learning is almost entirely focused on achieving good grades in SATs”. The following year, a parliamentary committee commented that “whilst some children undoubtedly find tests interesting, challenging and even enjoyable, others do not do their best under test conditions and become very distressed.” When the 2017 Education Select Committee inquiry spoke directly to pupils, they reported that “in general, the pupils were positive about taking SATs [as] they felt that SATs were a good opportunity to demonstrate what you knew”, although “some pupils told us they could get nervous or anxious about taking the tests”.

A survey by the polling firm ComRes in 2016 of 750 10 and 11-year-olds has provided one of the most comprehensive datasets on what pupils really think about testing in primary schools. When ComRes asked pupils how they felt about school tests, almost 60 per cent said they feel ‘some pressure’ to do well, with 28 per cent saying they felt ‘a lot’ of pressure and 11 per cent not feeling any pressure at all. When pupils were asked how they felt when taking tests at school and were given a list of words to choose from, the most common choices were ‘nervous’ (59 per cent), ‘worried’ (39 per cent) and ‘stressed’ (27 per cent). Even so, a notable (albeit smaller) proportion of pupils reported positive emotions such as being ‘confident’, ‘excited’ and ‘happy’. Perhaps surprisingly, after some pupils acknowledged that tests at school could make them feel nervous or worried, 62 per cent said they either ‘enjoy’ tests or don’t mind taking them. This indicates that primary pupils, like many adults, can understand the value and importance of tests even if they do not always relish them.

The question of what causes any stress or anxiety among pupils has also been investigated. When ComRes asked pupils who they would be most worried about knowing they did badly in a test, ‘my parents’ was named by 41 per cent – a bigger proportion than ‘my friends’ and ‘my class teacher’ combined. On a similar note, the CPR had earlier found that the effect of SATs on pupils varied considerably and depended, at least in part, on the actions of teachers and head teachers. For instance, previous research showed that “where schools have created a secure, non-threatening environment, high attainers begin to feel more confident and even exhilarated during the test period. However, under pressure, other pupils become demotivated and dysfunctional”. In 2019 Amanda Spielman, the Chief Inspector at Ofsted, stated that “good primary schools manage to run key stage tests often with children not even knowing that they’re being tested”, and testing “only becomes a big deal for young children if people make it so for them.”

The phonics check and multiplication check

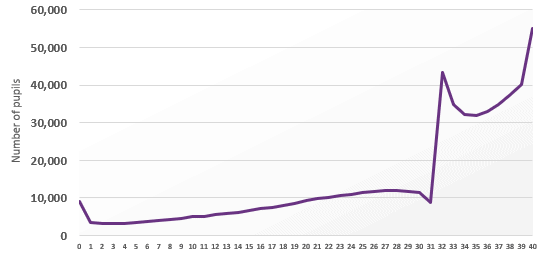

Since 2012, the ‘phonics check’ has tested whether Year 1 pupils can understand letters and sounds to an appropriate level, which would allow them to read many short words. The check lasts for about 5-10 minutes, during which time pupils must read a list of 40 words to their teacher. Pupils are scored against a national standard (‘pass threshold’), which has been set at 32 marks ever since the test was introduced. The pass mark was originally “communicated to schools in advance of the screening check being administered so that schools could immediately put in place extra support for pupils who had not met the required standard.” The national test scores in 2012 revealed – in the words of the DfE – “a spike in the distribution at a score of 32”. The same pattern of results – with a steep rise at the exact pass mark – has been visible in every subsequent year of the phonics check.

The number of Year 1 pupils (aged 6) in England scoring each possible mark on the first phonics check in 2012

Even though school-level results on the phonics check are not published, teachers and school leaders know that how well pupils are taught to read (including “how well the school is teaching phonics”) is classified as a ‘main inspection activity’ when Ofsted visit infant, junior and primary schools. In addition, for a school to be awarded a ‘Good’ or ‘Outstanding’ grade by Ofsted, inspectors must agree that, among other things, “staff are experts in teaching systematic, synthetic phonics”. The Ofsted inspection handbook refers to phonics 21 times in total. These demands offer a compelling explanation for the atypical results shown in the figure above. Such results also lend further weight to the argument that it is not possible for the phonics check to concurrently serve all the purposes for which it is being used – which includes monitoring individual pupils’ progress, school-level accountability, Ofsted inspections, national results and local authority standards.

The burden on schools has not been helped by the DfE interchangeably using the phrases ‘expected standard’ and ‘required standard’ to describe the pass mark. This lack of clarity emphasises how, despite there being no performance tables for schools’ phonics check results, the accountability system is almost intentionally placing considerable pressure on schools to ensure their pupils reach a certain level. When looking at the national proportion of pupils reaching 32 marks, there has been an improvement from 58 per cent in 2012 to 82 per cent in 2019. It is uncertain how much of this increase since 2012 is the result of genuine improvements in pupils’ ability to read as opposed to other factors such as greater familiarity with the test amongst teachers and pupils (a common occurrence in any new assessment). To illustrate the point, the proportion of Year 1 pupils passing the phonics check has increased by just a single percentage point since 2016.

From next summer, the new multiplication check (MTC) will require Year 4 pupils to complete an on-screen test of their recall of multiplication tables up to 12 x 12, with just six seconds to answer each of the 25 questions. Like the phonics check, a school’s results on the MTC will not be published but will be made available to Ofsted while the national results will be reported separately. Inevitably, the fact that Ofsted will see each school’s results draws this new test into the high-stakes accountability system, which is likely to reduce the accuracy of the MTC and thus compromise the DfE’s attempts to track national standards. That said, the decision not to introduce a ‘pass mark’ (unlike the phonics check) means there is less likely to be the same clustering of results around a specific score. The DfE claim that the MTC is necessary because “knowledge and recall of multiplication tables is essential for the study of mathematics and for everyday life.” That said, it is striking how the new MTC ignores addition, subtraction and division even though the National Curriculum says pupils should practice division and other related skills alongside multiplication. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the reception from stakeholders to the MTC has not been overly positive, with unions variously describing the new test as “unnecessary” and of “no benefit to pupils or teachers”.

Conclusion

Although existing primary school assessments appear to have made at least some contribution to improving standards, there are several weaknesses in the current arrangements that cannot be ignored. This report shows that primary schools are finding it increasingly difficult to focus on improving teaching and learning in the face of so many large and onerous assessments. Moreover, these assessments are often being used for too many purposes, which risks generating poor quality information for parents and policymakers. To overcome these issues, there is an urgent need to ensure that national assessments promote high standards but without distracting teachers and leaders from their core task of educating pupils.

To this end, this report puts forward a package of reforms (to be implemented by 2026/27) that aims to free up time for teaching and learning, reduce staff workload, track the progress of pupils and schools in a fair and proportionate way and monitor national standards over time. Three major shifts are required to achieve these goals over the coming years. First, there must be a concerted move away from the distorting and damaging effects of overbearing one-off tests such as SATs and instead use more frequent but shorter low-impact assessments. Second, pen-and-paper tests should be replaced by online assessments – as used in other countries – to make the tests more reliable as well as less burdensome for schools. Third, the one-size-fits-all standardised nature of SATs should be jettisoned in favour of ‘adaptive’ tests that provide a more personalised assessment. These changes would collectively represent a genuine step forward in terms of how, why and when we assess what primary school pupils know and understand. The report’s recommendations therefore offer a positive and ambitious vision for the future of primary assessment and accountability in England.

Recommendations

A new approach to assessment

- RECOMMENDATION 1: The current assessment system – including the full range of Key Stage 1 and Key Stage 2 SATs as well as the ‘reception baseline assessment’ and multiplication tables check – should be scrapped by 2026.

- RECOMMENDATION 2: From 2026, assessments for reading, numeracy and spelling, punctuation and grammar (SPG) should be delivered through online adaptive tests. These tests automatically adjust the difficulty of the questions to match a pupil’s performance, with a correct answer leading to a harder subsequent question and an incorrect answer leading to an easier question.

- RECOMMENDATION 3: Pupils will take the new adaptive tests approximately once every two years. As a result, the tests will provide regular updates on how pupils are performing throughout primary education. Each test will last for around 30 minutes. School leaders will be able to choose how to schedule these tests during the academic year.

- RECOMMENDATION 4: To encourage pupils to develop their creative writing skills throughout primary school, pupils’ writing will be assessed in Year 2 (age 6-7) and Year 6 (age 10-11) through ‘comparative judgement’ exercises across all primary schools.

- RECOMMENDATION 5: To support parents’ understanding of how their child is progressing through primary education, they should be provided with a report at the end of Years 2, 4 and 6 that shows their child’s most recent results on the new adaptive tests and writing assessments.

A new approach to school improvement and accountability

- RECOMMENDATION 6: To help benchmark their performance and identify areas for improvement, primary schools should be provided with an annual ‘profile’ of results for each year group to show how they are performing on the adaptive tests and writing assessments. The profile will also include national averages and local authority averages as well as the results achieved at ‘similar schools’ around the country.

- RECOMMENDATION 7: There will be eight headline measures of accountability for primary schools: Pupils’ average attainment and progress in reading; Pupils’ average attainment and progress in mathematics; Pupils’ average attainment and progress in spelling, punctuation and grammar; and Pupils’ average attainment and progress in writing. All eight measures will be reported annually for every primary school using descriptors from ‘well above average’ to ‘well below average’.

- RECOMMENDATION 8: The phonics check should continue in Year 1 (age 5-6) but the concept of a ‘pass threshold’ should be removed. In addition, Ofsted should no longer be provided with each school’s scores on the phonics check. These changes will reduce the likelihood of the results being distorted by having this assessment form part of the high-stakes accountability system.

- RECOMMENDATION 9: To ensure that national standards are measured separately from the performance of pupils and schools, the national standards for reading, numeracy and spelling, punctuation and grammar should be judged in future using ‘sample testing’. This will involve placing a small number of identical (or very similar questions) into the adaptive tests every year so that standards can be monitored over time.

NOVEMBER 2021